Columnist Younghee (Pseudonym)

Editor’s note

Do you enjoy watching movies alone? While I sometimes do, I find that films stay with me longer when I watch them with others. The conversations after the credits often linger longer than the film itself does. Plus, you get to share the popcorn. Today, I’d like to introduce a film that resonates with this sentiment.

Perfect Days poster / Source: t.cast

#INTRO

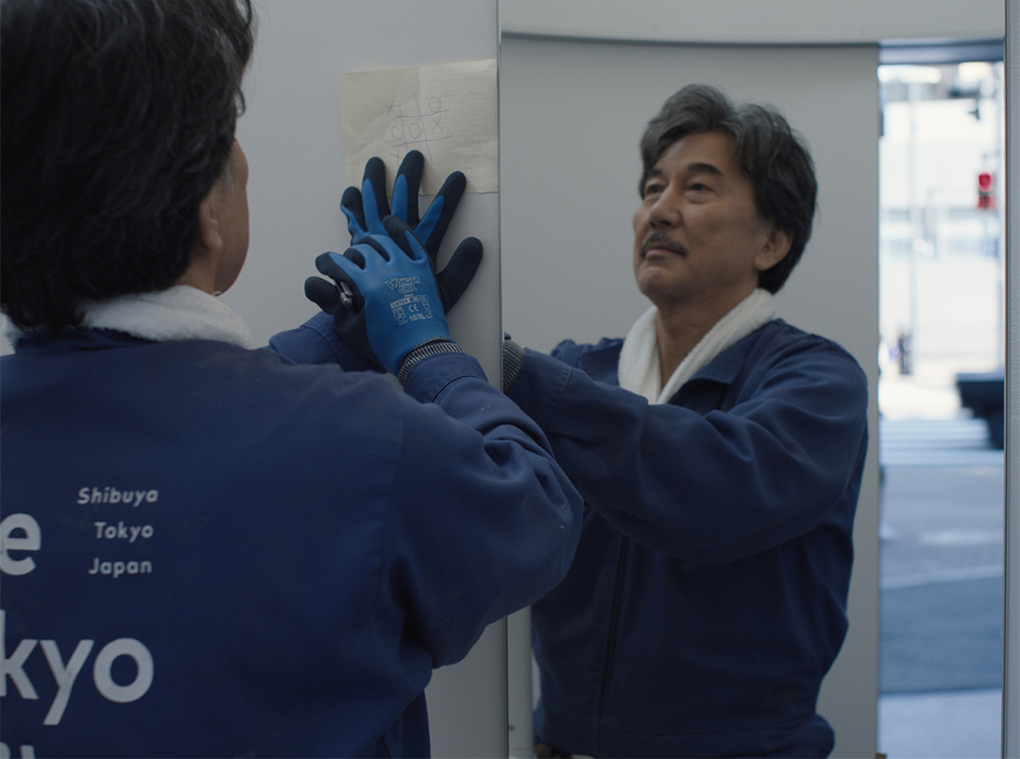

The film I’m introducing today is “Perfect Days,” which won the Best Actor award at the 2023 Cannes Film Festival. This Japanese-German co-production was created to promote the Tokyo Toilet Project, an initiative launched by Shibuya Ward to commemorate the 2020 Tokyo Olympics and Paralympics. German film master Wim Wenders was initially commissioned to make a documentary. But, after visiting Tokyo’s public restrooms and being deeply moved by the cleaning workers who kept them so clean, he pivoted to a feature film. Despite the sudden change of plans — with the script written in only three weeks and filming wrapped within 17 days — the result was nothing short of remarkable.

1 Days That Subtly Change Within Repetition

Perfect Days still / Source: t.cast

The film opens with a sequence showing the protagonist Hirayama’s repetitive yet subtly varied daily routine. Each morning, he wakes at the same early hour, tidies his bedding, washes his face, and shaves. As morning sunlight streams through the window, he waters a small potted plant and puts on his blue work uniform. He buys a canned coffee from a vending machine, climbs into his weathered minivan, and plays a cassette tape. With ‘60s and ‘70s oldies playing, he heads to a public restroom in Tokyo’s Shibuya district.

His work routine is particularly striking. Upon arriving at a public restroom, he begins by checking every detail, starting with the door handle, then the toilet, sink, bidet nozzle, and behind the urinals. Using a hand mirror, he inspects beneath the toilet bowl and meticulously cleans every corner with tools he’s made himself. If someone urgently needs the restroom, he waits outside and continues cleaning once they’ve left.

For lunch, he sits on a park bench, eating a sandwich, and photographs the sunlight filtering through the leaves (komorebi—木漏れ日) with his film camera. In the evening, he stops by a public bath to wash up and has a simple meal at his regular bar. Then he returns home, turns on a single light bulb, and finishes his day reading in the dimly lit room. His days follow a strict rhythm, yet small shifts — a change in weather, a coworker’s mistake, a fleeting smile from a passerby — make each one quietly unique.

2 Elements That Add Depth to Monotonous Days – Interactions with Others

Perfect Days still / Source: t.cast

At first, Hirayama appears to be someone who rarely speaks and lives quietly within his own routine. However, as the film progresses, his interactions with those around him make him three-dimensional. When Hirayama, who often wears a gentle smile, bursts into laughter, faces conflict, or even shows emotion because of the people around him, I could feel his world expanding and coming into sharper focus.

For instance, when his assistant Takashi asks, “Why do you work so hard at this job?” Hirayama doesn’t answer immediately. Instead, he silently wipes a handle and empties a trash can, responding through his “attitude.” This scene reveals that he’s not someone who merely settles into repetition, but rather someone who finds meaning and self-respect within it.

Perfect Days still / Source: t.cast

Another example is when his runaway niece Niko unexpectedly visits. Looking at the worn cassette tapes Hirayama listens to every day, Niko asks:

Niko: This is a cassette tape? What’s the (singer’s) name? Van Morrison? Is he on Spotify?

Hirayama: I wonder, where is it? That store.

This exchange isn’t simply about a generation gap—it shows how he accepts others’ worlds. Hirayama doesn’t dismiss Niko’s reaction; instead, he naturally embraces her curiosity. He nods along to the music she suggests, and we see subtle changes, like him turning on the radio instead of his cassette tapes during his commute. He doesn’t live enclosed within repetition, but quietly opens himself through others’ eyes. His life seems to be a multilayered landscape composed of intersections of relationships, not just simple routines.

3 The “Tokyo Toilet Project” Naturally Woven into the Film

Tokyo Toilet / Source – Tokyo Toilet website

The Tokyo Toilet Project, which serves as the film’s backdrop, wasn’t just a public works project—it was an artistic experiment showcasing Japan’s prowess as a design powerhouse. A total of 16 world-renowned architects and designers, including four Pritzker Prize winners, participated in redesigning 17 public restrooms throughout Shibuya Ward. Among them is even one designed by the creator of the Apple Watch — a detail that might make you smile.

These restrooms were designed with consideration not only for visual beauty but also for user accessibility and everyday experience. While the project overview might make the restrooms’ presence feel somewhat excessive, what’s interesting is how they’re used as natural elements of daily life in the film. A scene in which Hirayama demonstrates to a foreign tourist, with little dialogue, how the transparent glass walls become opaque when the door closes is a prime example. Rather than artificially showcasing the design, it was integrated into everyday life. This scene aligned well with the Tokyo Toilet Project’s philosophy of creating discrimination-free public spaces that accommodate diverse users, regardless of gender, nationality, disability, or sexual orientation.

#OUTRO

A “Perfect Day” Completed by Being Together

After the film ended, I found myself contemplating what a “perfect day” really means. While Hirayama’s days may seem the same, what completes his life is his relationship with the world around him. He writes responses to bingo puzzles hidden in restrooms, helps lost children, and watches with interest the dancing of a homeless person whom everyone else wants to avoid. In his daily life, beauty isn’t perfected in pristine conditions like a clean restroom, but in those quiet moments of friction with people and nature. Within repetition, he experiences the world differently each day and gradually recalibrates himself through relationships with others.

Ultimately, the “perfect day” the film speaks of seems not to be about flawlessness but about being connected. Routine is merely the framework of life, and what fills them are relationships with others. Perhaps, in cleaning the world each day, Hirayama is quietly cleansing himself too. I’ll close this column by reflecting with gratitude on the people around me who quietly transform me through the gentle repetitions of daily life.

Perfect Days still / Source – t.cast

✍ Perfect Days one-line review: The subtle beauty of everyday life revealed through connection

|

Younghee (pseudonym) |

|

|

Amorepacific

|

|

-

Like

0 -

Recommend

0 -

Thumbs up

0 -

Supporting

0 -

Want follow-up article

0