-

-

- 메일 공유

-

https://stories.amorepacific.com/en/the-resurgence-of-plastic-recycling-driven-by-esg-initiatives

The Resurgence of Plastic Recycling Driven by ESG Initiatives

Columnist

Kim Jeong-rim Amorepacific Safety

and Environment Support Team.

When querying various individuals about their interpretation of “environment,” the responses might diverge. Yet, invariably, they'd center on the notion of spatial and temporal cleanliness. It's a given that a pristine environment is foundational to enhancing our daily experiences. However, given their direct cost implications, environmental considerations become intricate in the corporate sphere.

Recent times have seen a rising prominence of ESG (Environmental, Social, Governance) management.

The environmental component, denoted by ‘E,’ can exert significant economic pressures and influence a company's external perception. This scenario can be double-edged — presenting challenges and opportunities — with certain trailblazing companies already capitalizing on it.

Given this context, I've undertaken to pen a two-part column series on environmental topics. The first segment focuses on plastic recycling, which is currently under the spotlight thanks to ESG. Historically, plastic recycling posed substantial challenges. However, through proactive ESG management and technological innovations, recycling and manufacturing are experiencing a transformation.

In this installment, we'll dissect the historical impediments to plastic recycling and introduce the cutting-edge solutions that have recently come to the fore.

The Surprisingly Low Rate

of Plastic Recycling

Here's a thought-provoking question:

“Can you recall a day entirely devoid of plastic?”

Be it ubiquitous household items such as shampoo, toothbrushes, and water bottles or more integral components like car interiors and public transit seats, plastic's presence in our daily routine is undeniable. Household plastics typically undergo a designated separation process for disposal. Yet, is it a common belief that every piece of plastic we segregate gets fully recycled? Cutting straight to the core: while they do undergo recycling, it could be in a different manner than most of us envision. What's the underlying narrative here?

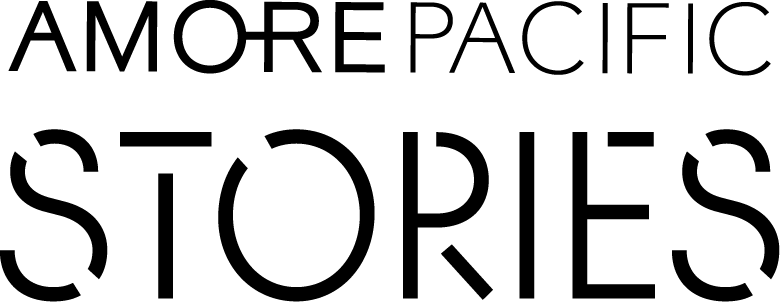

Source: Money Today

As of 2020's data benchmark, South Korea generated an annual plastic waste footprint of 9.6 million tons. From this volume, a mere 2.3 million tons — just 24% — is recycled in the conventional sense. The rest finds its fate in incineration or landfill. Intriguingly, specific plastic incineration processes in South Korea intended for energy recovery fall under the “thermal recycling” category, augmenting the recycling statistics. Incorporating this facet, an additional 3.8 million tons come into play, elevating the percentage to an overall 63.5%.

Source: Uiseong County, Asia Economy

Several years ago, there was an incident involving illegal dumping in Uiseong, often called the “Uiseong Garbage Mountain” case. The offenders offered waste disposal at rates lower than the market average, collecting trash and discarding it without permission in warehouses and open fields. The haphazard disposal led to significant waste management challenges, with recycling nearly impossible. One solution was incineration through cement businesses. Of the 208,000 tons of waste, 95,000 tons were processed as secondary materials in cement production. Waste handlers separated plastics, which cement companies introduced into their roaster kilns as an alternative to coal fuel.

In South Korea, cement companies incinerate a significant amount of plastic — around 1.7 million tons annually. With the complexities of establishing traditional incineration facilities in urban areas and the ever-growing volume of waste, these cement manufacturers have become an attractive solution. They handle plastics and other types of waste, such as wastewater sludge and used oils. However, despite receiving fees for waste processing, these companies, grappling with infrastructure investments and international coal prices, cannot solely rely on plastic processing as a revenue stream.

So, why has it been challenging to recycle plastics, and why has there been such dependence on incineration and thermal recycling?

Plastic: More Complex Than You Think

There is a vast array of plastics on the market, including PE, PP, PS, PET, PVC, PC, and FRP. While these varieties serve diverse purposes, each presents its unique recycling challenges.

1One primary hurdle in recycling is the inherent complexity of processing certain plastics.

Plastics are generally categorized into thermoplastics and thermosetting plastics. Thermoplastics melt with heat, making them easier to reshape. In contrast, thermosetting plastics burn when heated. Materials like fiberglass and carbon fiber within them make recycling nearly unattainable. For instance, FRP, a standard thermosetting plastic and composite material, is widely used in water tanks and fishing vessels. However, once discarded, it is usually treated like construction waste, ending up in landfills or crushed into aggregate.

Not all thermoplastics, however, are recyclable. PVC stands out as an example. During its melting process, PVC releases chlorine gas. Given that domestic air quality standards classify chlorine gas as an air pollutant, it must be treated before emission. Moreover, to enhance its flexibility, PVC incorporates additives known as plasticizers. Some of these, specifically the phthalate series, disrupt endocrine systems and are non-recyclable. Consequently, PVC is discarded as general waste.

Those plastics that are recyclable undergo a specific process. They are crushed into flakes, then mixed with new plastic material at particular ratios — a mixture called a “master batch.” This mixture is then used to produce fibers or containers. This process is commonly known as physical recycling.

2Another major obstacle in recycling (more accurately speaking, physical recycling) is the sorting process.

The higher the purity of a plastic type, the higher its recycling rate, making PE, PP, and PET the most preferred materials. However, achieving this requires distinct separation. Occasionally, plastics or films are labeled as “OTHER,” which signifies plastics composed of different materials or more than one type of plastic. Such composite plastics are usually destined for landfills or incineration due to their non-recyclability.

Color also poses a challenge. Taking the example of water bottles, while the bottle is made of PET, the cap is of PP material. Both are recyclable, but mixing clear PET with colorful caps degrades the recycled product's quality. In practice, density differences are exploited to filter out the PP, ensuring the purity.

Foreign materials further complicate the recycling process. Labels adhered with glue or printed containers disrupt the recycling process. Although soaking in sodium hydroxide can remove the print, the chemical is hazardous. This method also consumes significant water and risks producing microplastics. While solutions exist to address these challenges, their economic feasibility remains questionable.

Plastics offer undeniable convenience during use, but recycling them presents many constraints. Does this mean we must resort to incineration or landfill for all plastics, except those easily recyclable like PET bottles?

The Re-emergence of Plastic Driven by ESG

Driven by ESG imperatives, there's been a renewed interest in addressing challenging-to-recycle plastics.

We've entered an era where national commitments such as RE100 and carbon neutrality must be realized. With the traditional disposal methods via China becoming untenable and the European Union's stringent plastic packaging regulations, we need innovative approaches to meet these challenges.

Amorepacific, in collaboration with MYSC, is at the forefront, exploring ventures related to zero-plastic initiatives, underscoring the commitment to ESG-driven plastic management.

Ongoing research into eco-friendly plastics has produced promising outcomes. Let's spotlight three cases where nascent technologies have transitioned from research to commercial implementation under ESG's influence.

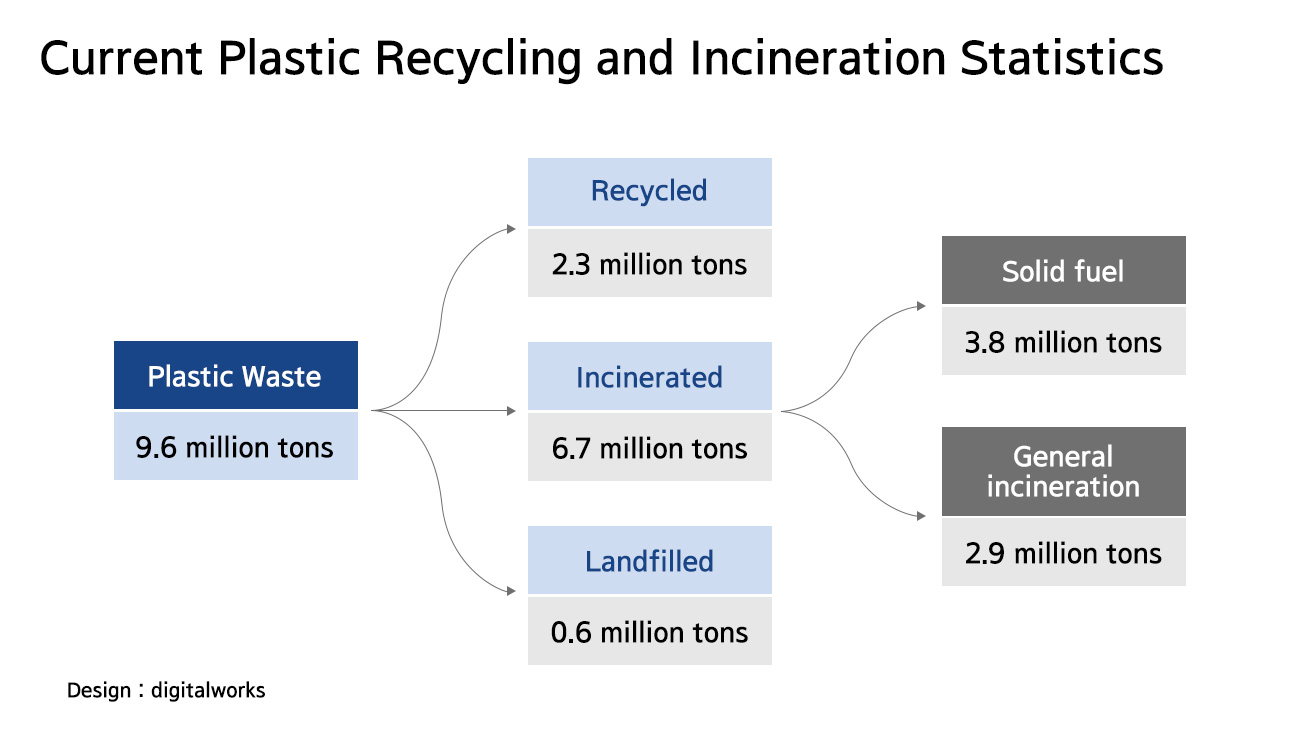

Source: SK Innovation, Aju Business Daily, CJ CheilJedang

1Chemical Recycling:

Chemical recycling, often termed pyrolysis, employs catalysts coupled with elevated temperatures to deconstruct molecular bonds. This process transforms plastics into foundational substances such as naphtha, gasoline, and diesel. While predominantly utilized as fuel, these outputs can also be channeled into petrochemical processes, generating plastics. These resultant plastics may be amalgamated with conventional plastic ingredients to enhance their content or exclusively produce 100% pyrolysis oil-based plastics. Initially constrained to research due to technical and financial challenges, the advent of ESG principles has catalyzed its evolution into commercial facilities. Even “OTHER” plastics can be recycled with this technique. Within our nation, leading oil refiners are progressively integrating pyrolysis oil, and there's a surge among petrochemical firms in establishing dedicated pyrolysis oil facilities.

2Material Simplification and Lightweighting:

Antecedent to recycling, there's a concerted effort to curtail initial plastic usage. The objective revolves around leveraging singular materials like PE, PP, and PET in container fabrication, emphasizing minimalist design, and trimming the volume of incorporated plastic. This initiative is notably active within the food and beverage domain. For PET bottles, prior practices involved affixing vinyl labels with potent adhesives. Today, the shift is towards user-friendly peel-off labels and milder bonding agents. Some beverages even eschew labels altogether, opting for embossed product identification instead. Numerous food and beverage conglomerates are collaborating with their petrochemical arms to pare down container plastic content. Concurrently, they invest in innovations to maintain structural integrity. The overarching ambition is dual-pronged: aligning with ESG benchmarks and realizing cost efficiencies via plastic usage reduction.

3Harnessing Natural Sources for Plastic:

This strategy champions bioplastics, subdivided into biodegradable, oxo-biodegradable, and bio-based plastics. Prominent among commercialized biodegradable plastics are PLA and PHA. PLA emerges from the polymerization of lactic acid, a byproduct of corn glucose fermentation. It's a favored material for 3D printing and has garnered traction in medical applications, especially as resorbable sutures. PHA, on the other hand, originates from microbial cells. Despite its modest production yield, its formulation through fermentation and refinement processes positions it as a frontrunner in meeting ESG criteria.

While research in eco-friendly plastics and recycling methodologies has been around for a while, the urgency for large-scale commercial adaptation wasn't always there. Factors like economic constraints and prevalent disposal routes through countries like China played a role. The onset of the pandemic initially saw crude oil prices plummet, making new production more economical. However, the collective global push to curtail plastic usage has redefined the economics of the equation.

We're in the pioneering phases, and obstacles remain — quality assurance, technical feasibility, or potential regulatory conflicts. But the horizon looks promising with the world waking up to the plastic dilemma and diving headfirst into the recycling industry.

Amorepacific was ahead of the curve, championing eco-friendly initiatives even before ESG discussions became mainstream in 2020. The vision? To someday house all their offerings in 100% recycled plastics and present them to our customers.

-

Like

4 -

Recommend

3 -

Thumbs up

0 -

Supporting

0 -

Want follow-up article

0