-

-

- 메일 공유

-

https://stories.amorepacific.com/en/amorepacific-light-and-texture-asias-third-path-to-beauty

Light and Texture: Asia’s Third Path to Beauty

Columnist

Juyoung Reu LANEIGE BD Team

Editor's note

In today’s global beauty market, Eastern and Western concepts of beauty reveal distinctly different sensibilities. We see a coexistence of Eastern aesthetics that bloom like gentle shadows and Western aesthetics that shine with the clarity and brilliance of intense light. The beauty philosophy of Korea and the broader East Asian tradition has long valued something beyond the visible—what we might call ‘gyeol,’ the texture and grain that carries the emotion and depth inherent in objects and skin. It contemplates the textured ridgelines of mountains softly bathed in sunset light.

This column explores the metaphors of ‘light’ and ‘texture’ to examine the emotional landscape of Eastern beauty, with a focus on Korea. By exploring the philosophical roots of Eastern aesthetics, nature-inspired expressions, and analyzing the visual codes and case studies of Asian beauty brands, we aim to offer an opportunity to contemplate a ‘third path to beauty’ that unfolds in a direction distinct from the Western one. Through this lens, we have explored together how Eastern aesthetics is establishing itself as a new aesthetic paradigm rich in emotional and philosophical depth.

1 The Roots and Emotions of Eastern Aesthetics: Nature, Harmony, and Depth

Eastern aesthetic is rooted in ancient philosophical traditions, placing nature and harmony at its core. Confucianism has long emphasized human virtue and harmony (和), valuing the virtues of restraint and balance in both art and daily life. Meanwhile, Daoist thought championed wu wei zi ran (無爲自然)—the natural beauty that exists without artificial embellishment—developing an aesthetic that follows nature’s course rather than artificial manipulation. Buddhism went a step further, awakening us to beauty within transience through the concepts of wu chang (無常, impermanence) and kong (空, emptiness). Since all forms and moments are temporary, the emotions and appearances of this very moment become precious, and meaning dwells within empty spaces. The aesthetic concept of yugen (幽玄), formed within the sphere of Japanese Zen Buddhism, means “subtle, profound beauty that is not directly revealed but leaves deep resonance,” while kanso (簡素) refers to “elegant simplicity that expresses maximum beauty with minimal elements.” Thus, throughout Eastern aesthetics flows the insight that beauty can be found in the invisible and the empty.

Tea room embodying Eastern aesthetics/Source: Pinterest

A frequently cited anecdote that contrasts Eastern and Western aesthetics is found in Japanese philosopher Kakuzō Okakura’s (岡倉覺三) work, “The Book of Tea.” Through the aesthetics embedded in tea culture, he introduced Eastern beauty to the West, expressing that the Eastern tea ceremony (chado) is rooted in the pursuit of imperfection. True beauty emerges not from perfectly radiant beauty, but when something is slightly lacking and empty, creating space for the heart to fill those gaps. While Westerners might see shabbiness in a tea cup, Easterners perceive the beauty of negative space and simplicity. He said, “We find beauty not in things themselves, but in the shadows they cast and the empty spaces between them”—demonstrating how profoundly Eastern sensibility values suggestion, metaphor, and lingering resonance. Rather than illuminating everything with dazzling light, beauty emerges when it is revealed subtly, like half-veiled moonlight, stirring the imagination and emotion.

Indeed, in Zen aesthetics, ‘the beauty of emptiness (kong)’ is mentioned as central. Empty spaces and voids that might appear hollow are integral parts of art. This runs counter to Western aesthetic standards, which have traditionally pursued symmetry and precision. From a Zen aesthetic perspective, things that are too smooth and complete lack vitality; true natural beauty breathes within the slightly askew and rough. Korean traditional aesthetic operates similarly, finding more warmth in the natural splits of tree rings than in polished jade, and discovering beauty in the traces of time and human touch rather than in pristine newness.

This Eastern sensibility is reflected in the aesthetics of emotion, as evident in Korean concepts such as han (恨) and jeong (情). For instance, in Korean culture, beauty is often discovered not in joy and splendor but in melancholy tinged with han and quiet emotions. The somewhat lonely yet lingering melody of pansori, the beauty of autumn leaves falling gently, and a cup of chrysanthemum tea—these possess a different texture from the bright and distinct beauty of the West. Thus, Eastern aesthetics focuses on the atmosphere felt in secrets and spaces not brightly revealed before our eyes.

2 The Aesthetics of Light and Shadow, Smoothness and Texture

Comparison of Eastern and Western paintings (Left) Shin Saimdang’s Grape Painting / Source: JoongAng Ilbo (Right) Claude Monet’s Still Life with Apples and Grapes / Source: rtprinta

The contrast between light and shadow is a frequently used metaphor when discussing the differences between Eastern and Western aesthetic sensibilities. Western art and beauty culture have long featured prominent contemplation of ‘light.’ From Renaissance paintings that employed chiaroscuro to give figures dimensional prominence, to modern beauty trends that utilize contouring and highlighters to accentuate facial contours, beauty has been emphasized through the use of intense lighting and contrast. Junichiro Tanizaki, a representative writer of modern Japanese literature, expressed it this way: “The West constantly pursues enlightenment toward progress, but Eastern beauty lies in shadows and subtlety.” Indeed, the gentle luster of lacquered bowls and the gleam of gold leaf seen in the interior of a traditional Japanese home creates an entirely different atmosphere than when viewed under fluorescent lighting. Korean hanok architecture similarly comes alive when sunlight entering through the wooden floors mingles with the dimness inside rooms, revealing the grain of the wood. It is within this contrast of light and shadow that Eastern beauty reveals its texture.

If Western aesthetics has pursued ‘radiant beauty,’ Eastern aesthetics can be seen as emphasizing ‘permeating beauty.’ This is the sensibility that values jade or nephrite, which holds light subtly within, more highly than dazzlingly brilliant diamonds. Korea’s long-preferred porcelain-like luminous (yungwang) skin follows the same principle. Rather than flooding the skin with light to make it gleam, the ideal has been a moist luster that seems to emanate from within. This represents the pursuit of clear, subtle light that differs from the Western aesthetic of matte, bronzed skin. In Korea, the glow is not a flashing brilliance but rather the radiance that emerges from healthy hydration.

Meanwhile, ‘texture’ (gyeol) is an indispensable concept in Eastern aesthetics. Texture refers to the inherent structure and patterns of objects, such as tree rings or stone markings. In Korean, it’s used to describe skin texture, fabric grain, and other surface qualities. In traditional crafts, Eastern artisans emphasized bringing out the natural texture of materials. Even in wooden bowls coated repeatedly with lacquer, the wood grain had to show through, and when dyeing silk fabric, the natural texture of the fibers had to be revealed. This is an aesthetic that respects inherent patterns and textures. However, since industrialization, under the influence of Western aesthetics, this has evolved in the direction of polishing surfaces to create smooth, lustrous finishes. As smoothness and flawlessness came to be regarded as premium qualities, skin beauty also strongly tended toward establishing porcelain-smooth skin without freckles or wrinkles.

I wonder if our obsession with smoothness causes us to miss the depth of life felt in rough but meaningful elements of existence—wrinkles, scars, shadows. Perfect smoothness that erases all roughness and traces seems to eliminate the marks of life, making beauty monotonous and unnatural.

When viewed through these two pairs of contrasts—light and shadow, smoothness and texture—we can conclude that while Western aesthetics pursued intuitive beauty through bright, clear elements like oil paintings, Eastern aesthetics sought beauty that gradually permeates the viewer’s heart like ink wash paintings through subtle shadows and natural textures. Of course, in today’s global beauty trends, Eastern and Western elements are increasingly fused; however, underlying differences still persist. Eastern beauty embodies imagination about the unknown and tolerance for imperfection. This aesthetic brings freshness to the world today and is gaining attention as a third aesthetic philosophy.

3 Textural Differences in Eastern and Western Aesthetics: Lines and Curves, Illumination and Resonance

Japanese traditional ceramic repair technique—kintsugi (金継ぎ)—accepts and emphasizes breakage as part of beauty/Source: Pinterest

The West has pursued distinct contours and contrasts, seeking immediate sensory satisfaction. Their beauty is rooted in the proportions of classical sculpture and the clarity of physical form, with expressions that are direct and explicit. Asia, by contrast, contains beauty within curves and flow, negative space, and suggestion. It highlights relaxed silhouettes that embrace the harmony of curves, as seen in the hanbok, Korea’s traditional garment. The Eastern perspective values an aesthetic of texture, which finds elegance in concealment rather than revelation.

If the West has placed ‘youth’ and ‘freshness’ at the center of beauty, the East has treasured ‘time’ and ‘inner condensation.’ The Japanese spirit of wabi-sabi (侘寂)1) gives birth to new beauty even within imperfection, like the golden seam repairs (kintsugi) of cracked ceramics. This resonates with an attitude that fully accepts the texture created by time, just as plants leave their marks on branches through the seasons.

1) Wabi-sabi: A traditional Japanese aesthetic and philosophical concept that refers to the spirit of discovering beauty in imperfection, transience, and simplicity.

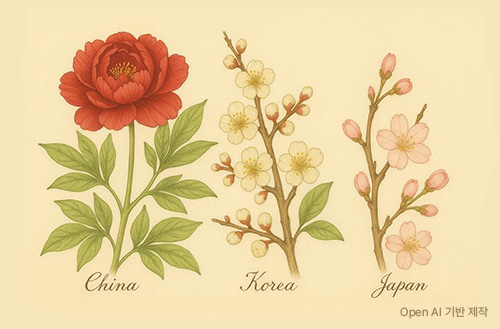

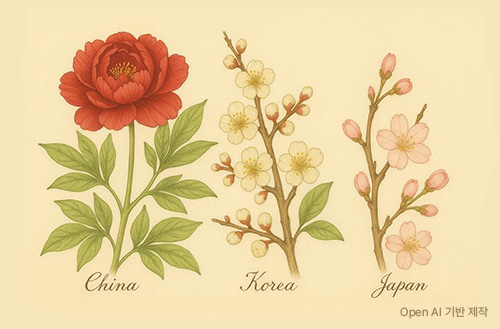

4 The Textures of Asia’s Representative Three Nations: The Aesthetics of China, Korea, and Japan

Peony, White Plum Blossom, Cherry Blossom/Source: ChatGPT Generated Image

China, Korea, and Japan, which form the core of Eastern aesthetics, share similar philosophical roots while each possesses distinct aesthetic textures. Their differences are like the leaves of different trees growing from the same forest, each interpreting the world of beauty in its unique way through its distinct light and texture.

Chinese beauty is intense and extroverted. Imperial traditions and brilliant color aesthetics emphasize strong presence and authority, highlighting ‘visible power.’ Visual languages such as red, gold leaf, and bold brushstrokes accentuate external grandeur. To express it through flowers, Chinese beauty is like a blooming peony—majestic, splendid, and possessing the power to command the center.

Korean beauty is based on harmony and resonance. ‘Restrained abundance’ is contained in texture that holds emotion, sentiment within negative space, and luminescence that emanates from within. It respects delicate textures, such as skin grain, and regards the traces of time and the flow of emotions as beautiful. Korean beauty is like plum blossoms that hold fragrance even in the depths of winter—restrained yet profound, capturing inner light.

Japanese beauty is an aesthetic of moments and imperfection. Concepts like wabi-sabi, yugen, and mono no aware (物の哀れ)2) emphasize disappearance, shadows, and resonance, evoking emotions within emptied spaces. Sensation takes precedence over form, suggestion over results. Japanese beauty is like cherry blossoms that bloom luxuriantly and soon scatter, leaving resonance in their final moments rather than in the moment of existence.

China, Korea, and Japan each express ‘light and texture’ in different ways. China weaves beauty through intense sunlight and solid forms, Korea through clear, hydrated luminescence and soft textures, and Japan through shadows and momentary sensations. This represents a difference in philosophical and emotional rhythms, which contributes to the depth of Asian aesthetics.

These currents of Asian aesthetics are revealed more concretely through each nation’s representative beauty brands.

2) Mono no aware: Meaning that beauty leads toward dissolution, it refers to the quiet sadness felt in transient beauty like cherry blossoms.

Source: Florasis Official Instagram

Florasis (花西子), one of China’s premier luxury beauty brands, embodies traditional Chinese art and poetic sensibility through modern beauty, utilizing visual languages of flowers, embroidery, and classical poetry in its product designs. These designs are inspired by ancient cosmetic culture and feature sophisticated colors with subtle textures.

Source: Sulwhasoo Official Instagram

Korea’s Sulwhasoo, based on ginseng aged over long periods and traditional medicine philosophy, has presented a path of beauty that connects inner balance with outer radiance. Under the philosophy that ‘skin is a vessel that holds the traces of time,’ it expresses the texture of skin as one of the most noble forms of beauty.

Source: Shiseido Official Website and Instagram

Japan’s Shiseido is a brand that fluidly harmonizes Eastern and Western aesthetics. At the intersection of natural flow and scientific exploration, it respects the skin’s rhythm while pursuing the beauty of the five senses through sensual packaging, fragrance, and formulations. Meticulous detail and completeness reflect Japan’s delicate aesthetic sensibility.

In this way, each brand conveys the sensation of ‘texture’ in its language, representing the aesthetic of Asia.

5 A Third Sensibility: Not East versus West, but Aesthetic Convergence

Contemporary beauty now extends beyond the simple contrast of East and West toward a ‘third sensibility.’ At its center lies not merely national identities, such as K-beauty, J-beauty, or C-beauty, but a philosophy that values the pace and rhythm of life and the ways we connect with nature through emotion. Asian beauty routines transcend simple skincare steps to become embodied as ‘ritual.’ Caring for the skin becomes a form of caring for the mind, and beauty extends to the inner breath beyond the external surface.

Today’s beauty is moving away from simply ‘beauty to be seen’ toward ‘a way of living.’ Beauty is coming to resemble not a single radiant flower but the ecosystem of a forest that embraces diverse textures.

Epilogue

The Beauty of a Blooming Forest

Asian beauty is not a single flower. It is situated closer to a forest, where plants of various textures grow together in harmony. Some have large leaves, others carry a deep fragrance, and still others sway quietly in the wind. Yet all of them together form one ecosystem. Light touches each texture differently, and each texture reflects that light in its way. That is the actual depth of Asian aesthetics.

Light and texture are beings that bring each other to life. The forest of sensibility that blooms from their harmony will be the future of beauty that Asia conveys to the world, and now we must cultivate that forest with even greater care.

So that standards of beauty are not simplified, yet texture is not erased, allowing light to spread more evenly as it meets the air.

While essence flows as one, beauty is never singular. In this forest where diverse textures coexist, just as ‘light’ and ‘texture’ bring each other to life, true beauty must also exist while embracing love.

Reflecting on that spirit, I wish to conclude this column with an ancient Latin phrase.

In necessariis unitas, in dubiis libertas, in omnibus caritas.

Unity in essentials, freedom in non-essentials, love in all things.

* References

1. Kakuzō Okakura, The Book of Tea – A representative essay introducing Eastern aesthetics to the West. Expresses beauty blooming within ‘imperfection.’

2. Jun’ichirō Tanizaki, In Praise of Shadows – Emphasizes Japanese aesthetic sensibility that loves darkness over brightness, subtlety over splendor.

3. Soyeon Park, “The Emotional Codes of K-Beauty and Eastern Aesthetic,” Journal of Aesthetic and Cultural Studies, 2020.

4. Jihyeon Kim, “A Comparison of Chinese, Korean, and Japanese Aesthetics,” Asian Cultural Studies, 2018.

5. Hyosoon Jin, “A Study on the Concept of ‘Texture’ in Korean Traditional Beauty,” Journal of the Korean Society of Aesthetics and Art, 2016.

-

Like

0 -

Recommend

0 -

Thumbs up

0 -

Supporting

0 -

Want follow-up article

0